There Was Stage, 18th Century, Poetry

Report of an Aesthetic Realism Lecture by Eli Siegel given on June 10, 1973

By Carol McCluer

It’s with great pride and gratitude as a person and actress that I report on the class in which we studied via tape-recording a lecture Eli Siegel gave June 10, 1973, titled, “There Was Stage, 18th Century, Poetry.” This was thrilling, hopeful, inspiring education about something Aesthetic Realism explains for the first time: that the art of acting is an expression of the deepest desire of every person—to like the world. Mr. Siegel began by saying:

In this matter of having liking the world seen vividly and truly, the art of acting is perhaps the most useful, immediate art. It can be defined as the being able to be someone else beautifully, or something else: a desk, a tree. It has in it that great faculty and that great hope that is in everyone to be someone else. It happens that hope has not been kept to. Actors have used this faculty for selfish purposes. Consequently, actors have been seen as narrow. But the fact remains that the desire to be someone else is a great thing.

This is tremendously important! I have learned—and it changed my life—that the desire to become someone else is central in our liking ourselves, and that to see what another person feels is the beginning of kindness and justice.

Mr. Siegel read first what he said was a “passage about acting as eloquent as any” in a review written by Thomas Talfourd (1795-1854) who, he said, was an important person of the Romantic period. Talfourd wrote the intense and moving play, Ion, about which Mr. Siegel spoke in another talk. Talfourd was also a judge, a biographer of Charles Lamb and friend of Dickens. Said Mr. Siegel, “I don’t know anything that shows the desire to be kind, of acting, better than this by Talfourd.” He writes:

It is only in the theater, that any image of the real grandeur of humanity…is poured on the imaginations, and sent warm to the hearts of the vast body of the people….Their horizon is suddenly extended from the narrow circle of low anxieties and selfish joys….Surely the art….which gives the poorest to feel the old grandeur of tragedy….which makes the heart of the child leap with strange joy, and enables the old man to fancy himself again a child—is worthy of no mean place among the arts which refine our manners by exalting our conceptions!

“I am reading this,” said Mr. Siegel, “because it shows the desire Walt Whitman wrote about—the desire to be something other than we are….It is in keeping with the Aesthetic Realism idea that the greatest desire of a person is to like the world, and you cannot like the world unless you are it.”

And then, he gave a great instance of a person becoming the world from Hamlet, a play he looked at with the most loving, scrupulous, mighty thoughtfulness, and about which he wrote his critical masterpiece, Shakespeare’s Hamlet: Revisited. He read the scene in Act II in which Hamlet sees a player show great emotion as he tells about a woman of ancient Greece, Hecuba, seeing her husband, Priam, slain by Pyhrrus. Said Mr. Siegel:

…Shakespeare is taken by the problem of acting….[In this soliloquy, Hamlet is asking,] Why can this player get into such a turbulence about Hecuba? It does say an emotion that is impersonal—that is, an actor’s emotion—can be greater than a personal emotion.

And he read this from Act II, scene ii:

Hamlet: Is it not monstrous that this player here,

But in a fiction, in a dream of passion,

Could force his soul so to his own conceit

That, from her working, all his visage wann’d,

Tears in his eyes, distraction in’s aspect,

A broken voice, and his whole function suiting

With forms to his conceit? And all for nothing!

For Hecuba!

What’s Hecuba to him, or he to Hecuba,

That he should weep for her?

Hamlet, Mr. Siegel said, didn’t have the complete answer to that question. And he continued: “The question of what is acting, what is sincerity, how does acting show a person and something beyond the person, is a large one, [and] the 18th century was central.”

I learned that in the 18th century acting began to flourish as never before. There was a major shift in acting style from something more formal and artificial, to a desire for emotions to be shown more naturally and with truthfulness.

The great actor David Garrick was a force in London at this time, as well as others, including Peg Woffington, Henry Woodward, Sarah Siddons, Susanna Cibber, Hannah Pritchard, John Philip Kemble and Kitty Clive. There was a lively interest in acting, and much public debate about performances at such theatres as the Drury Lane and Covent Garden.

This was shown through what Mr. Siegel discussed next: a long poem titled The Rosciad, written in 1761 by Charles Churchill, a person he saw as notable in the history of theater and poetry. The title comes from the name Roscius, who was the greatest comic actor in Rome. The Rosciad—which Mr. Siegel said is the only poem in English literature consciously about acting—is a poem in couplets describing with vividness, criticizing, and at times praising, many of the actors and actresses of the day.

Churchill’s descriptions are so alive—they tell of the problems actors have had through the years: what to do with one’s hands, one’s voice, one’s expressions, and the various mistakes one can make in deportment and gesture. We learned that at the time this poem appeared, it was read by all of London and caused a great uproar, including among the actors—some threatened to fight Churchill. What Mr. Siegel saw about the goodness of The Rosciad as poetry, and the value of Charles Churchill as poet, has not been seen anywhere else.

In one passage, Churchill satirizes an actor named Thomas Davies, and points to a defect in his acting having to do with diction. Churchill writes:

Statesman all over!—in plots famous grown!—

He mouths a sentence as curs mouth a bone.

“That has remained, not being able to say words clearly,” commented Mr. Siegel. And he noted that there was an actor named Holland, who, Churchill says, “has a tendency to look upward too often…at the skies.” Churchill writes:

Next Holland came,—with truly tragic stalk

He creeps, he flies,—a hero should not walk.

As if with Heaven he warr’d, his eager eyes

Planted their batteries against the skies;

Mr. Siegel said humorously, “The art that has characters imitate everyone most is acting. As soon as an actor sees another doing something, he starts doing it.” And he continued, speaking of more physical manifestations: “There are many ways of sighing; groans are many. Acting tells about emotion. To have emotion, whatever it is, is interest in the outside world.” Eli Siegel was lovingly exact on the subject of emotion, and had such enthusiasm for acting: the way he became someone else as he read from a play or story was beautiful.

Continuing with The Rosciad, he read another couplet in which Churchill notes the tendency in an actor, Yates, to forget his lines. His wife was an actress, and they were, Mr. Siegel said, the “most notable husband and wife team at that time.” Churchill writes:

Lo, Yates!—Without the least finesse of art

He gets applause; I wish he’d get his part.

And Churchill is critical of Mrs. Yates, and other actresses of the time. Said Mr. Siegel, “[T]he problem of how good an actress is and how good she looks is a big question of the 18th century.” Churchill writes:

What’s a fine person, or a beauteous face,

Unless deportment gives them decent grace?

Bless’d with all other requisites to please

Some want the striking elegance of ease;

The curious eye their awkward movement tires:

They seem like puppets led about by wires.

Commented Mr. Siegel, “So composition is part of acting, too. You use your body as others use a canvas, others use an orchestra.”

In the discussion following the lecture, I was very affected when Chairman Ellen Reiss asked, “If [a person] is too still, not able to have motion in her face, does that have to do with an inability to like the world? How central is [liking the world to acting]? There should be a real critical looking.” I am grateful to be in the midst of this critical looking.

by Sir Joshua Reynolds

It was wonderful hearing Mr. Siegel discuss many other passages from The Rosciad, including about other famous ladies in the 18th century. Hannah Pritchard played in William Congreve’s only tragedy titled The Morning Bride, and Churchill liked her very much; he also valued greatly David Garrick as actor. Garrick, said Mr. Siegel, “had a great disadvantage. He was just a trifle too short for Hamlet; however, he got away with it.” Churchill writes towards the end of the poem:

When the pure genuine flame by Nature taught,

Springs into sense and every action’s thought;

Before such merit all objections fly;

Pritchard’s genteel, and Garrick’s six feet high.

This poem, Mr. Siegel said, “is still a repository of what people liked in the 18th century.”

In the last part of this class, Mr. Siegel looked at a poem by a 19th century poet, William Collins, titled The Passions, An Ode For Music. He said it is “one of the strangest poems in any language” but that “it’s a good poem. It is about the expression of emotion.” In it, Collins personifies the passions—Fear, Anger, Despair, Hope—and tells how they wanted to express themselves through Music. The poem begins:

When Music, heavenly maid, was young,

While yet in early Greece she sung,

The Passions oft, to hear her shell,

Throng’d around her magic cell,

Exulting, trembling, raging, fainting,

Possest beyond the Muse’s painting:

By turns they felt the glowing mind

Disturb’d, delighted, raised, refined;

Said Mr. Siegel, “It happens all the arts are about expressing emotion. The question is whether every passion shown by the actor, or simply had in life, has in it some attitude to the world.” Collins, he said, “has the passions quite busy, saying ‘Please express us.’” And he gave humorous and deep examples of the passions Collins writes of, and lines that could express them.

He said: “In order to show you’re a good actor, you have to learn how to tremble and…how to be disconcerted. “What! There’s a person in the barrel!” And about Raging: “Tell the landlord he can go to hell!” Fainting, he said, means “the desire to give up but be sweet about it. A lady had to learn how to swoon gracefully.” And he said, “Fear is a very big thing. …Can you have fear without being surprised?…One of the things you have to learn in theater schools is how to recoil in fear. You could almost recoil yourself off the stage: “What is this?” Then: “You have to learn how to be delighted. In musical comedy, you are delighted in a straw hat, which helps.”

Before I studied Aesthetic Realism, I was terrifically mixed up about what my purpose was as I went to auditions and got various parts. I used acting mostly as a way to push myself forward, not as something to study and love, and I was very nervous and felt like a faker. I love Aesthetic Realism for teaching that acting has a big, ethical purpose I can respect myself for, and that it is beautifully continuous with what my purpose should be in my everyday moments. How different this is from the way acting generally is seen, and I passionately want every actor to know it!

Mr. Siegel said at the end of this great lecture:

The large question is, Is there a deep desire in every play, with all an actor does, to like the world, to honor a part? And insofar as any actor honors a part, is that a way of honoring the world?

I love this question, and Mr. Siegel showed with the greatest scholarship and relish that the answer is, Yes! “It’s a good act to be an actor,” Mr. Siegel said to conclude, “because it honors the world.”

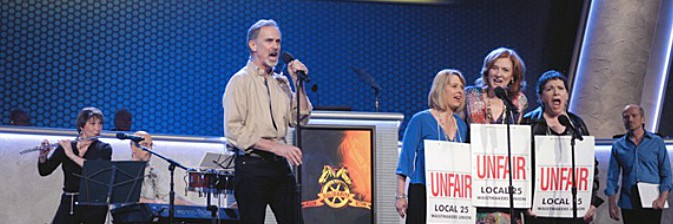

First presented at the Aesthetic Realism Foundation, New York City.